From the Gulf South Frontlines to Germany: Accelerating Progress on Gas Exports

This article was written as part of our 2024 Impact Report.

Elida Castillo was just a few months into her job leading Chispa Texas, a Corpus Christi -based grassroots organizing group, when she got the invitation: A delegation of environmental justice leaders from the Gulf Coast of Texas was heading to Europe to talk about how gas fracked in Texas, processed along the Gulf Coast, and exported to Europe as liquified natural gas (LNG) was harming their communities. Two weeks later, she was on the ground in Germany sharing stories with environmental campaigners and the media about the industrial toxins poisoning the air and water in her hometown and participating in protests along with leaders from the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas and others.

That visit in July of 2021 and several more like it that followed has grown into a powerful trans-Atlantic collaboration that is highlighting the human rights abuses and climate and environmental impacts associated with US gas exports to Europe and putting European banks on the defensive.

“For me, this is so important because if we are able to reduce demand for LNG consumption overseas, it takes wind out of the sails of the argument that LNG is needed to solve the world’s energy problems,” said Castillo, “and that lessens the harms being inflicted on our communities.”

Elida Castillo, center, speaking to the press club in Brussels

Andy Gheorghiu, a German policy and campaign consultant focused on gas, saw an opportunity as soon as he met the Gulf South activists. “We have very good documentation about the climate impacts of [LNG],” he explained, “data and records that we can use to confront our decisionmakers and the media. But now we can actually connect them with the impacted people, and that is something that is extremely valuable.”

Gheorghiu helped organize and is coordinating a regular strategy meeting between European activists and leaders in Texas and Louisiana, and delved into some research to better understand the flow of gas and finance between the regions. Armed with this new data, he organized the first in a series of speaking tours in 2023, bringing US frontline groups to meet with German policymakers, European parliamentarians, international bank leaders, media reporters, academics, and local activists. The results were inspiring.

By the end of 2023, the group succeeded in getting LNG added to a list of commodities with potential human rights violations in Germany’s Supply Chain Act, and the EU moved to limit allowable methane emissions from fossil fuel imports. Then in January, just a month after world leaders agreed at the COP28 meeting to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems,” the group helped organize 60 European leaders to send a letter to President Biden.

“Europe should not be used as an excuse to expand LNG exports that threaten our shared climate and have dire impacts on US communities,” they wrote, noting that with declining European demand, further investment in fossil fuels “will quickly become stranded assets.” The next day, Biden announced publicly that the Department of Energy (DOE) would pause approvals of certain LNG export facilities pending review of the so-called public interest criteria used to evaluate them.

Frontline groups celebrating the DOE pause.

This win, the result of national and international campaigns coming together with frontline voices from the Gulf and other impacted communities at the center, put the unchecked growth of gas exports into the public spotlight. Movement groups now saw an opportunity to push for progress on two fronts: permanent policy changes at the DOE, and investment changes at key banks and insurance companies — many of them based in Europe — whose dollars were behind these projects.

“Projects that kill our communities would not exist without the backing of financial institutions,” said Roishetta Sibley Ozane, an organizer and activist from Southwest Louisiana who was a leading figure in the DOE pause and also participated in the European tours.

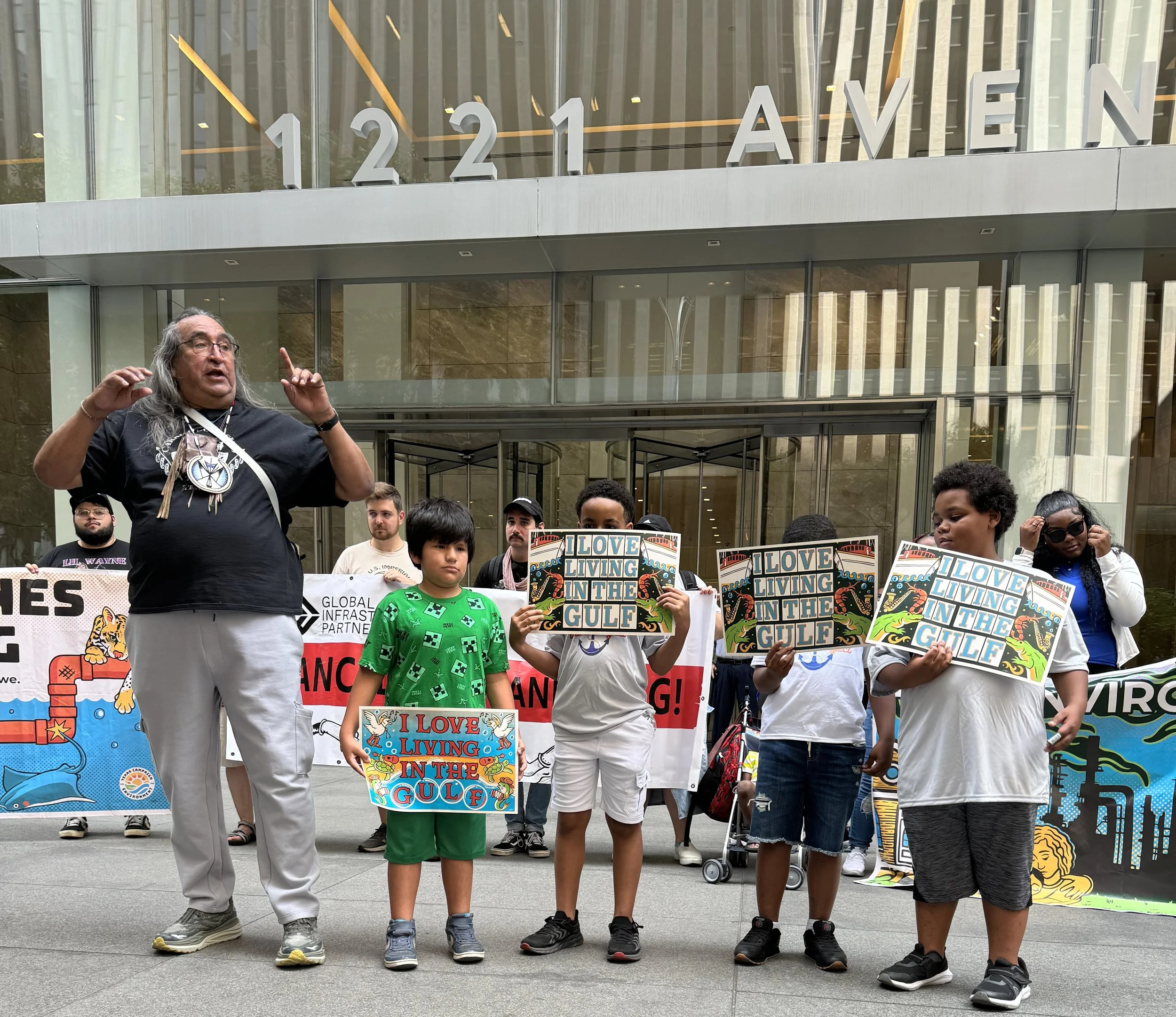

Juan Mancias of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Tribe of Texas with Gulf Coast residents at a Summer of Heat event. Photo courtesy of Texas Campaign for the Environment.

Building on the foundation of the trans-Atlantic collaborative, Ozane and her organization, The Vessel Project of Louisiana, teamed up with Texas Campaign for the Environment (TCE) to start the Gulf South Fossil Finance Hub. This new group is bringing together frontline groups that were already putting pressure on international finance institutions supporting harmful projects in their communities, and connecting them with larger national and international campaigns like Stop the Money Pipeline that have a wealth of data and strategic insights. In summer 2024, the Hub brought over 150 people from multiple Gulf South groups to participate in the “Summer of Heat” campaign, a nationally organized pressure campaign targeting the New York headquarters of key fossil fuel financiers.

“It’s one thing for the head of a big national climate group to go into a meeting with bank executives, and entirely another for someone like Roishetta Ozane to go in and tell her story,” said Jeffrey Jacoby, the Hub’s co-founder at TCE. “That’s a big part of our theory of change.”

This strategy has been used successfully for years in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Frontline groups there, along with their European allies, have stopped and stalled three gas export projects to-date, most recently winning withdrawal from the Rio Grande LNG project by international insurance giant Chubb. The goal of the new finance hub is to help connect, resource, and amplify these efforts.

“What I’ve learned is that it’s really an ecosystem model, putting on the pressure from all sides,” said Jacoby. “What we want to do with the Gulf Hub is cultivate more and more voices from the Gulf South. If we can provide them opportunities and platforms through the collaborative work we do, we will make the movement more powerful.”